by Natalia Timmerman Blotskaya | Mar 19, 2023 | Musings

What is freedom to you? A writing prop recently popped up in my digital diary.

For somebody who was born and raised in the USSR, whose place of birth is present-day Belarus, infamous for its dictator, my answer to that question is from the place of experience of what freedom is not.

What is freedom to me?

Freedom is choice.

At the ballot box—like 27 candidates in the parliamentary elections, not one and only.

My body—my choice—and I shall bear no interferences.

In who or what I want to believe in or worship. I choose to believe in no deity and worship no one. And I am not sorry.

Freedom is pluralism.

A right to an opinion, however non-conventional, inconvenient or non-mainstream.

On vaccines, on regimes, on wars, on policies, on rights of minorities and loot of majorities.

Pluralism is an expression of your stance and should not be treated as a thought crime from an Orwellian dystopia or become a self-righteous crusade to prove everyone is wrong. We’ve had too many of those in human history: religious, colonial, racial and ideological.

Freedom is a multiverse where a multitude of stories, opinions and angles, including those of our opponents and adversaries, can co-exist. Censoring people out of discourse is not freedom.

Freedom is the right to evolution—individual and societal.

Redemption without cancellation. Freedom is the right to change. Isn’t it how we, as a collective society, advanced from the Dark Ages?

Sure, our ancestors screwed up big time. Acknowledge the evils, reflect and put the lessons into perspective. One cannot wipe slates of history clean by cancelling them.

We, as beings, evolve throughout our lives. Our opinions and positions change as we learn through exchanges and interactions, come across new information and discoveries and experience life. What I thought was right 35 years ago isn’t what I deem right today. Back in the day, subsisting on an ideological diet, I was a fierce proponent of socialism. America and the entire Western world were my enemies. The pain of disillusionment and deceit is still acute. Should I be cancelled for the views I once held?

What is freedom to you?

The crux of this question is in to you? I’ve answered. You don’t have to agree with any of it. And that to me, is freedom.

by Natalia Timmerman Blotskaya | Nov 18, 2022 | Writer’s journey

Walking down the creative writing path as a mature student calls for a rational response to a field of literature that I have long neglected—poetry, even though—What is the point of poetry if I am writing prose?—played like a looping record in my mind.

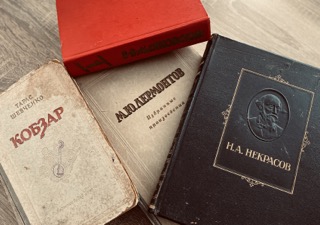

Memorising and reciting the poems of many Russian and Soviet poets in the Soviet school I once attended, was a mechanical act of obedience. Prose and poetry analysis, like everything else, was conducted through the ideological prism. When I disavowed ideology, Mayakovsky’s Soviet citizen poems still rang in my ears. And ever since, poetry remained an undecipherable realm of literature for me, even though I loved it for its performative and artistic appeals, especially when pontificated along the axes of social, cultural and literary referencing.

Now, in the formal setting of the university programme, the assertive brutality of inferencing and the aural appeal of succinct and packed-with-meaning splendour had me in awe with some poems, while others left me in tatters of bewilderment. Regardless of the underlying complexities of this genre, here are three personal takeaways from my beginner’s encounter with poetry.

- Finding anchoring imagery in poetry isn’t that different from that of prose.

You scout the landscape of your imagination for the right and fitting description of the selected object, emotion and interaction that is conveyed through allusions and inferences. One particular exercise, ‘riddle me,’ unleashed the child in me. We were tasked to describe our favourite thing as if it were a living creature.

- Lineation in poetry could be used as an effective editing technique in prose, especially for short, word-count-sensitive pieces.

In finding poetry in prose exercise, we lineated prose. First, at a sentence-per-line level, and eventually breaking down to poetic beats—phrases and words—an ingenuous manipulation that provides a magnifying-glass clarity for wordsmithing opportunities.

- Brevity is at its finest in poetry. The economy of language is pertinent and relevant across all literary genres. Conveying profound themes in a laconic and concise manner is an invaluable skill.

There is a poet in all of us. I had to believe that going forward, surrendering to the novelty of the experience of creating new worlds of words, having no fear but a child’s curiosity, getting messy with words, and disregarding the rules while listening to that bit of your soul.

What is the point of poetry if I am writing prose? Words are like bees cross-pollinating all genres of literature; the bigger your literary prairie, the more honey is gathered.

by Natalia Timmerman Blotskaya | Sep 19, 2022 | Writer’s journey

Why writers write is the mother of all questions.

You might not have your answer at the onset of your writing journey, or your answer is in flux as your relationship with the craft evolves. Ponder gently, resolutely; ponder with intention.

Here are the three tips on finding your why.

-

Scale down

Do your search for an answer pertinent to a specific piece of writing you are currently working on—why do you want to write this? Let it germinate. Distil. Repeat with another piece of writing until it’s convincing, concise and clear.

-

Be curious

Let your favourite authors inspire you—how did they answer their big why?

For example, one of my favourite authors, Jeanette Winterson, in her memoir Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? said:

It’s why I am a writer—I don’t say ‘decided’ to be, or ‘became’. It was not an act of will or even conscious choice. To avoid the narrow mesh of Mrs Winterson’s story I had to be able to tell my own. Part fact part fiction is what life is. And it is always a cover story. I wrote my way out.

George Orwell intellectualized his answer in his essay Why I Write. He narrowed it down to four pillars: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm.

Another one of my cherished authors Lidia Yuknavitch, in her memoir The Chronology of Water, said:

Writing, she is the fire of me. Where stories get born from that place. Where life and death happened in me. She carries me and will be the death of me.

-

Write

As mundane as it sounds, writers write. Write like there is no tomorrow, write as if your life depends on it, write till you no longer can. Write impulsively, write for self-reflection, write to make sense of that insatiable burning that urges you to write. Trust yourself, and the answer will present itself.

Happy writing!

by Natalia Timmerman Blotskaya | Jun 27, 2022 | Musings

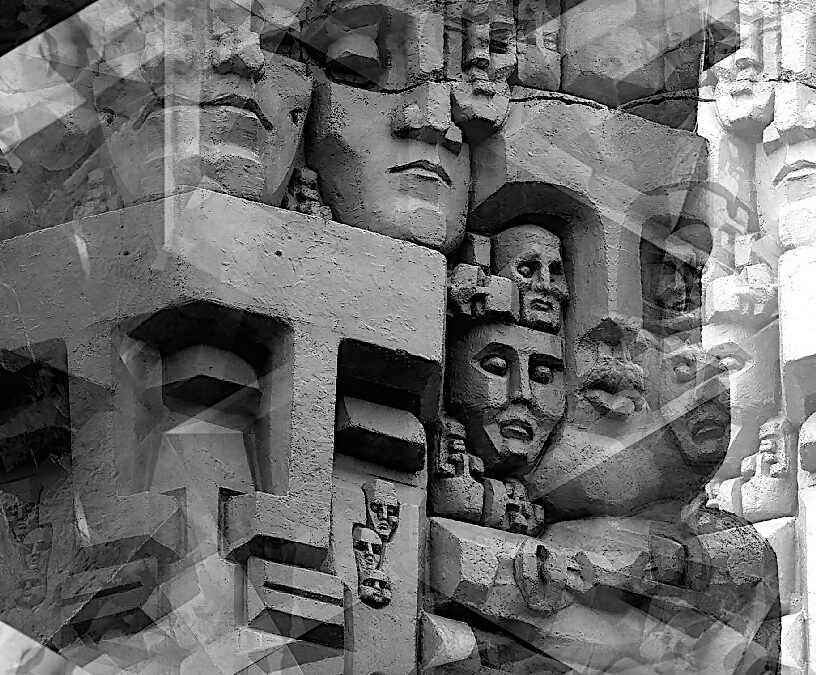

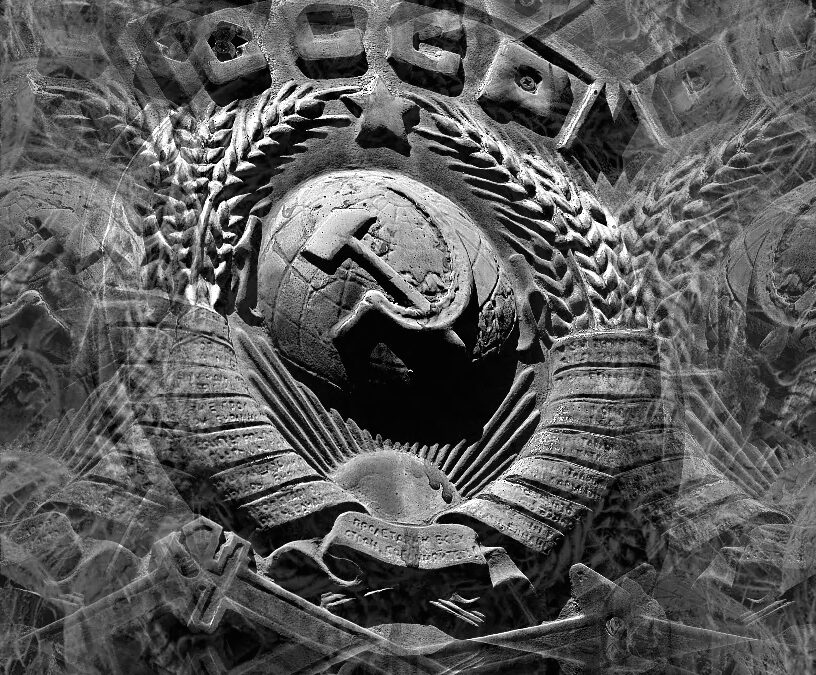

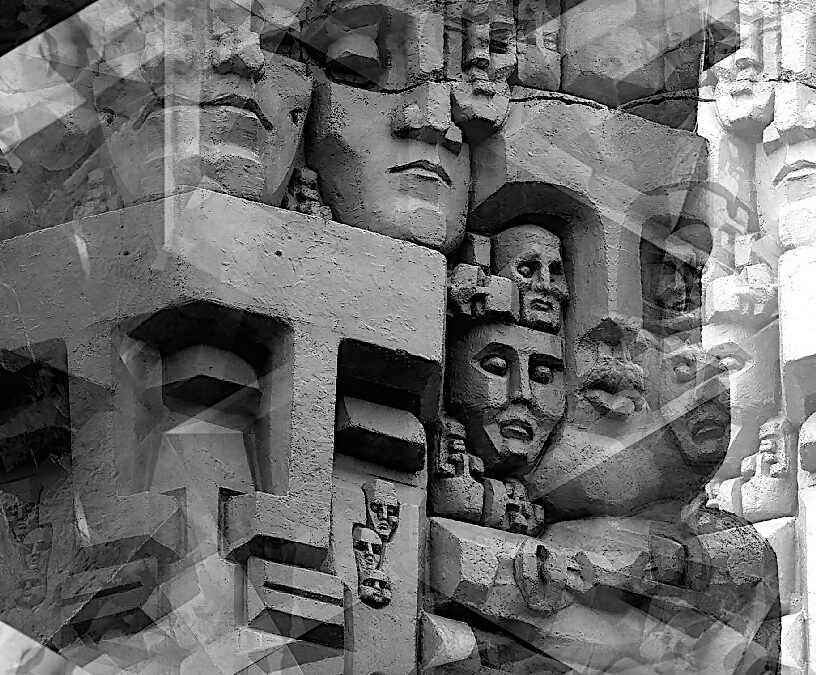

I came from a country that no longer exists.

I left the rubbles of the once almighty USSR, but it never left me. It, the invisible force of my upbringing, permeated every corner of my being in subtle whispers and reflective bouts. I spent decades purging seared memories of that life.

Having enough food to eat has been my life’s prerogative. It gently taps me on the shoulder, ‘Look, there is two for one.’ It still murmurs in the supermarket to take three bags of flour instead of one, just in case. ‘Lucky we have a Soviet mum,’ our boys said at the first Covid lockdown, praising our stocks of essentials.

No food ever goes to waste, as ancestral tales of the Great Ukrainian famine replay in my mind. It’s called mindful consumption.

I live with a heightened awareness of waste. Mine came from scarcity and since stayed. In the age of abundance, I reuse plastic bags, fold away used foil, and do not throw away things but find new homes for items and clothes. They call it environmentally friendly.

It screws with my style and sense of fitting together and is a source of general apathy for that aesthetic obsession. I go with what I like, unguided by philosophies, rules, or fashion.

It urges me not to succumb to the new ideology- Consumerism. It screams at the sight of long lines to a clothing store on the first day after the lockdown. Are you that desperate to part with your money? I had to consume everything that came my way to return to the origin- being pragmatic in my consumption.

It hurts me to think of how many people perished in the crevices of my country’s collective memory without a trace for a thoughtcrime, for daring to think differently about their experience of being pimped by the government reality. A thoughtcrime is back in vogue.

My fear of the police is on a cellular level. I still flinch at the sight of the police car or police patrol on the street. I think different. What if it‘s for me?

It guides my life with a general suspicion of one’s good intentions. What’s the catch?

I refuse to follow. I followed enough.

I have contempt for too many rules and anything too organised; it impedes one’s creativity. Rule-breaking got us to graduate from the USSR. After all, we are all equal in our inequality.

It soothes me with the hope that extracting the good, the bad, and the in-between of your upbringing enables you to tell Your story.

by Natalia Timmerman Blotskaya | Jun 2, 2022 | News

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, millions of Ukrainian civilians, mainly women and children, rushed to the exit West. My childhood friend, Lidia, from my mother’s Ukrainian village in the Zhytomyr region, was among them.

My close friend Micaela joined me in my urge to help Lidia’s extended family sheltering in the hostel in Zawichost, Poland. We raised funds and donations and visited a community of 100 displaced women and children. On the long drive home, we pledged to stay committed to these people and found our grassroots initiative, JourneyHome2022.

For more on our efforts and journey, follow us on https://www.facebook.com/JourneyHome2022/